|

How does a lad from Wellington College who never medalled at the Maadi Cup become an Olympic champion - a member of the New Zealand rowing eight in Tokyo who shocked Germany and Great Britain to capture gold after battling through a repechage to make the final, lucky to be in Japan in the first place?

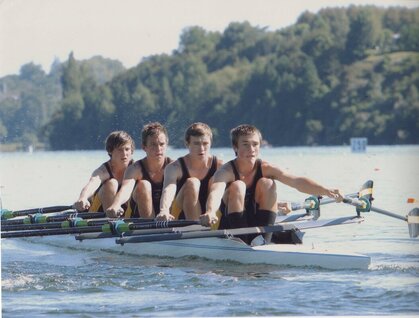

The story of Phillip Wilson is one of perseverance, trial, error, improvement, and some good fortune, but first let’s deal with the nicknames. “I’ve got a few, 'Bilbo Baggins', 'Neanderthal', 'Front Row Phil' as in I'm always in the front of photos. I can take it, I’ve had it for years,” Phillip said. He sits in the sixth seat of the New Zealand boat, the shortest and lightest individual in the engine room which contains the crews’ heaviest and most powerful rowers. “It’s not exactly the most traditional place. We tried a dozen to 15 combinations before the games. It definitely didn’t come easily, but once we were locked in we knew this was the line-up that got us fastest down the course. It was a process of trial and error. I sat in every seat of the boat before the Olympics.” Flashback to 2010 and Phillip Wilson is Year 9 at Wellington College. He is a natural in any sport he turns to. His father Greg Wilson, a self-employed builder and “sports nut,” recalls Phillip kicking a soccer ball as soon as he could walk, swinging a golf club aged three, and flourishing at rugby, basketball and cricket. However it's rowing that appeals most. “I started down there in Wellington Harbour when I was 13. It wasn’t the best place to learn given the notorious wind and rain, but I pushed my way through that and worked my way up the grades. I've always enjoyed the challenge of pushing myself to the limit." His first Maadi Cup was in 2011 and two seventh place finishes in B finals were hardly eye-catching results. However, an incident prior to the regatta suggested Phillip was made of sterner stuff. He was challenged by a senior to his first erg, a rowing machine race set to a specified time. Phil lost narrowly, reduced to sickness from exhaustion. “It was properly two or three years before I realised I had some ability. I was top of the group at school and thought I’d try and push for some representative teams. I made a North Island team when I was 16 and was picked in the National junior squad a year later. “Rowing is the toughest team sport out there because you’ve got to be doing everything in sync. Playing other sports helped me handle the dynamic of an eight.” His final Maadi Cup in 2014 represented massive improvement. His best result was fourth aboard a new boat in the U18 singles sculls, but that doesn’t illustrate his total impact. “He seemed to be the lynchpin in all the crews. He stroked the pair, four, and eight as well as racing the singles. With the help of fundraising I brought him a new boat. His tenacity and grit was so impressive, Greg Wilson recalled. “The Wellington College rowing team was an amazing group of people. Typically, you’d start with a dozen boys and there would be two or three left by Year 13. We still had a dozen guys after five years. I drove them all over the country and we became great mates. There’s no doubt their encouragement and friendship helped Phil.” Representing New Zealand in the men’s double at the 2014 World Junior Championships in Hamburg and medaling twice with Petone at the National Club Championships were major breakthroughs. At the club regatta he was a 17-year old in crews whose average age was 27. The oldest competitor was 37. Meanwhile the U23 New Zealand men’s eight struck gold with back-to-back triumphs at the 2013 and 2014 World Championships. Suddenly after years in the wilderness the black boat was back. Phillip spent two seasons with Central Rowing Performance Centre and a year at the University of Otago. He returned to the New Zealand team in 2016 as part of the U23 men’s coxed four. The crew won gold at the World Championships in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Phillip linked up with Tom Murray in 2018 to win the National senior pairs title. Now based at the National High Performance Centre in Cambridge he had a seat in the New Zealand eight. Stephen Jones, Brook Robertson, Alex Kennedy, Joe Wright, Finn Howard, Isaac Grainger and Caleb Shepherd from the U23 World championship winning boat were all gone. “I’m not sure how many guys were a part of this team. We had different crews each year, interchanging positions. There were a whole lot of people involved in this journey,” Phillip said. “We all trained over the summer trying to make our boats go faster. Trials come around and it’s a lot of stress. It’s not a nice time of the year. You put pressure on yourself to perform. It’s all part of the process.” New Zealand’s processes weren't working. The 2018 World Championships were a let-down and the eight was almost abandoned until two-time Olympic champion Hamish Bond insisted otherwise. “He was the one who lit the candle again. We’d kind of given up on the eight after the World Champs but he’s like, I want to do the eight in Tokyo. Were like we weren’t going to do that, but okay. We thought it was going really well. We had a couple of decent results in Europe but missed out on Olympic qualification and that was devastating.” It was Bond’s convincing of the “higher ups” that earned a final lifeline. The last chance regatta was held in Lucerne in May 2021. A fast start caught the field napping and the Kiwis resisted a late surge by Romania. A fast beginning was typically unusual for New Zealand. In Tokyo a sluggish first heat saw New Zealand consigned to the repechage. “Repechage was a good thing for us because we didn’t put out our best result in the heat. We had to go away for four days and make sure we were executing our race plan and rhythm. We proved in the repechage we were pretty quick." The Olympic final was held on July 30 and the only certainty was it would be quicker than normal. “Traditionally we race on freshwater. Tokyo Bay is salt water. It’s really hot. The temperature was properly 27 degrees which means fast conditions. There was a cross tailwind heading down the course too which meant we weren’t battling a head wind. “We went through the first 500 in third. We knew we weren't the fastest crew and the first 500 was almost damage control, trying to get our rhythm. From there we started to move up to the Germans. Through the 1000 it was a pretty tight race. You kind of have a sense of where you are, but you don’t fully know. “I knew we were in front at 250. I saw the finish line go underneath us like the line you follow on TV. They have a results board on one side and it said NZL first. It’s pure elation. You put everything into the race. You're spent afterwards but you get that adrenaline buzz because of the moment.`` Greg was watching with the parents of the crew at the Cloud in Auckland. Only Covid prevented him from being there in person. The decision for all the parents to assemble together was made via a conference call two months before the Games. “New Zealand is always the most well supported team internationally. The parents all share a special bond and we all decided we’d pretend we were in Tokyo. I still haven’t come off the high of Phillip winning. It’s a feeling hard to describe. Eight years ago Phil wrote down a goal he wanted to be an Olympic champion. He’s done it and I’m so proud of him,” Greg said. New Zealand last won Olympic gold in the eight in 1972. It was the first time ‘God defend New Zealand' had been played.” “Their win has always been mythical in the rowing community. They’ve been looked up to and we dreamed of repeating them," Phillip said. "We didn’t have much correspondence with them up until the games but after we won we got a message from one of them acknowledging all of them. It arrived by text to one of the coaches. It was passed down the bus on the way home. We were pretty thankful for the message. It said, ‘Congrats you are now carrying the mantle.’" Greg recalled five years earlier when Phillip won his World U23 title some of his old schoolmates literally needed carrying. “I got a call on WhatsApp from a number I didn’t recognise. I answered and there was all this noise in the background. The call was from New Zealand and it must have been 3 o'clock in the morning. It was his mate Daniel Petrovich and he slurred, ‘I love you, Henry’s crying.”’ Rowing Eight Maadi Cup Highlights Tom MacKintosh (Lindisfarne College) - Won a silver medal in the U16 double sculls in 2013 and a bronze in the U17 single sculls in 2014. Tom Murray (Marlborough Boys’ College) - Won four titles in a double and quad boat between 2010 and 2012. Hamish Bond (Otago Boys’ High School) - Head Prefect in his final year Bond won a full set of medals in his last regatta in 2003. His 69 consecutive victories with Eric Murray for New Zealand is a world record. Michael Brake (Westlake Boys’ High School) - Westlake had a serious tilt at the Maadi Cup itself which is the boys U18 coxed eight. They were third in 2011 and 2012. Daniel Williamson (King’s College) - Moved from Howick College to King’s and in his last two years of high school earned four gold and two bronze medals. He was selected to compete in the Junior men’s coxless four at the 2017 World Junior Championships in Trakai, Lithuania. Daniel teamed up with Thomas Russel, Matt MacDonald and Ben Taylor to earn a silver medal. Shaun Kirkham (Hamilton Boys’ High School) - Enjoyed a stellar career twice winning the Maadi Cup and Springbok Shield. Shaun followed the Rowing New Zealand pathway through the Rowing Performance Centre system with Waikato. Sam Bosworth (Christ’s College) - Was a member of the 2012 crew which won the Maadi Cup. Only Whanganui Collegiate School with 17 titles have won the Maadi Cup more often than Christ’s. Wellington College Olympic History Wellington College (Phillip Wilson's former school) has produced 18 Olympians and enjoyed semi-regular medal success. Arthur Halligan (1901-1902) was a New Zealander who competed for Great Britain at the 1908 London Olympics in the 110 metre hurdles. He finished second in his heat but only the winners advanced to the semi-finals. He would become national champion in the same event in 1915. Harry Wilson (1911-1912) was flag-bearer at the 1920 Antwerp Olympics. He competed in the 110-metre hurdles and was fourth in the final, 0.5 seconds away from a bronze medal. Wilson won nine national titles. Boxer Ted Morgan (1921-1922) was Wellington’s first gold medalist. He won the welterweight class at the 1928 Amsterdam Olympics. Despite competing throughout the tournament with a dislocated knuckle he beat Raúl Landini from Argentina in the final. The plummer was the 1925 and 1927 National Lightweight champion and won 26 of 28 amatuer fights. Wellington’s next gold medalist was Gregory Dayman (1961–1965). He was a member of the 1976 hockey team who beat Australia in Montreal. He later became a successful architect in Auckland. Dave MacCalman (1975) in javelin and Tim Prendergast (1996) middle distance running were Paralympic champions. George Cooke (1918-1921) was the first rower from Wellington College to attend the Olympics. He competed in the four who missed out on the finals in Los Angeles in 1932. Robert Hellstrom (1991-1993) was a member of the coxed four crew in Sydney 2000 while George Bridgewater (1996-2000) and Peter Taylor (1997-2001) proved to be dynamic international competitors with each winning bronze medals at the 2008 Beijing and 2012 London Olympics respectively. *Two members of the 1972 rowing eight competed in the Hutt Valley. Ross Collinge was a Petone club member and Dick Joyce was from the Hutt Valley club. |

OrganisationCollege Sport Media is dedicated to telling the story of successful young sportspeople in New Zealand

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed